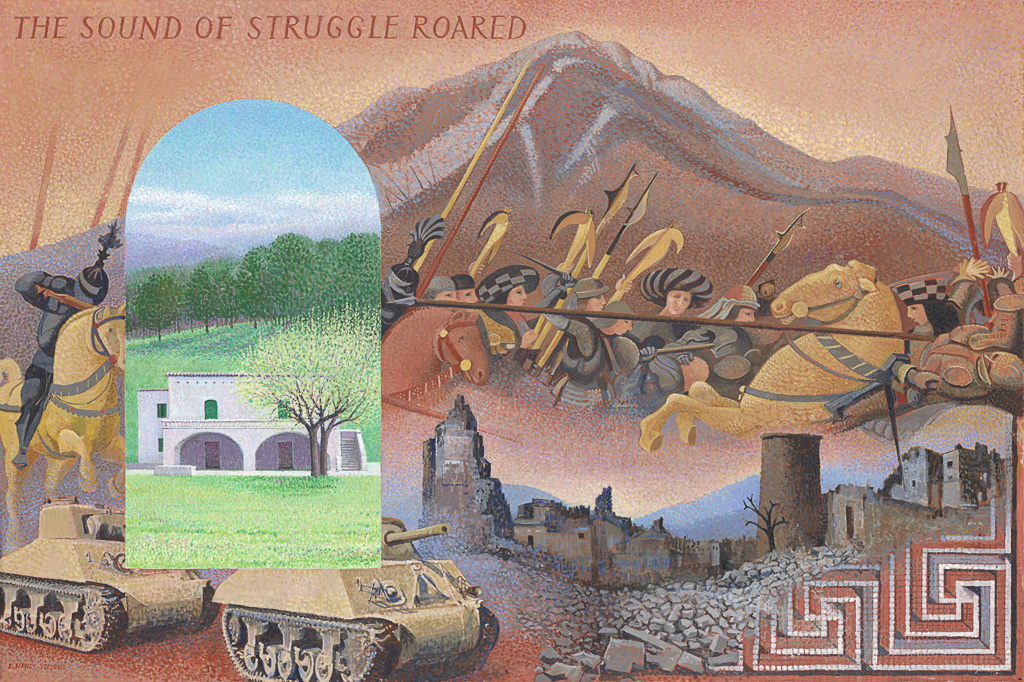

MIGNANO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

MIGNANO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

Exhausted from fighting a skillful enemy in pitiless weather, Canadians with the British Eighth Army and the US Fifth Army were stopped in winter 1943 at the Mignano Gap, the invasion route since earliest recorded history. Ancient towns and villages lay in ruins.

An advance of 10 kilometres in seven weeks in mountains, mud, rain, snow and swollen rivers cost the Allies 20,000 casualties. Mignano was part of a temporary defensive line in front of fortifications considered so impregnable the Germans called it the Hitler Line.

“If the cost of breaking this temporary line is remembered,” wrote Eighth Army infantry officer Fred Majdalany who took part in the battle, “and the time it took to do it, an idea may be gained of what was going to be involved when the finest German troops, the geography of Italy, and the full fury of mid-winter conspired together in defense—as now they were about to do.”

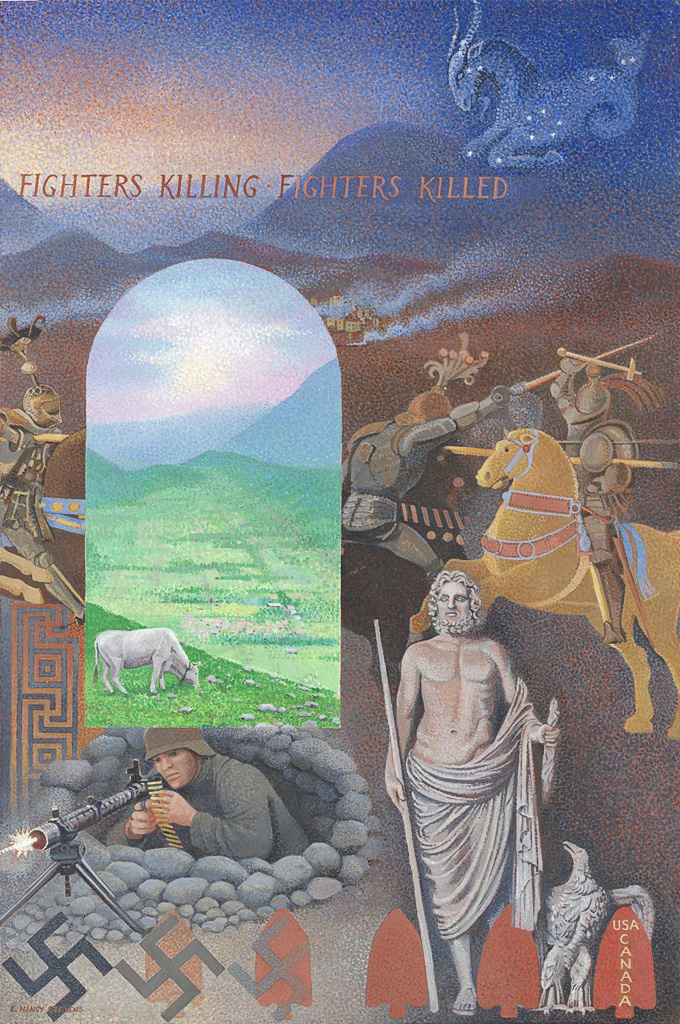

HILL 720 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

HILL 720 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

Six hundred Canadian and American commandos of the 1st Special Service Force were ordered to capture mountain strongholds on each side of the Mignano Gap which a division had failed to take in repeated attacks with heavy losses. The ancient Roman god, Jupiter, giver of victory, may have offered his blessings.

Two hours after scaling cliffs with ropes in December darkness and driving rain, they defeated the Germans on Monte La Difensa. At 3 a.m. of Christmas Day, they climbed Monte Sammucro, descended on a ridge named Hill 720 and wiped out the German position in four hours.

“We had a tremendous advantage fighting in the mountains,” said Tom Gilday, a Canadian commander. “We not only had the advantage of having trained in the mountains, we also had the clothing and equipment that went with it, and no other soldier had that.” The Germans named them the Devil’s Brigade.

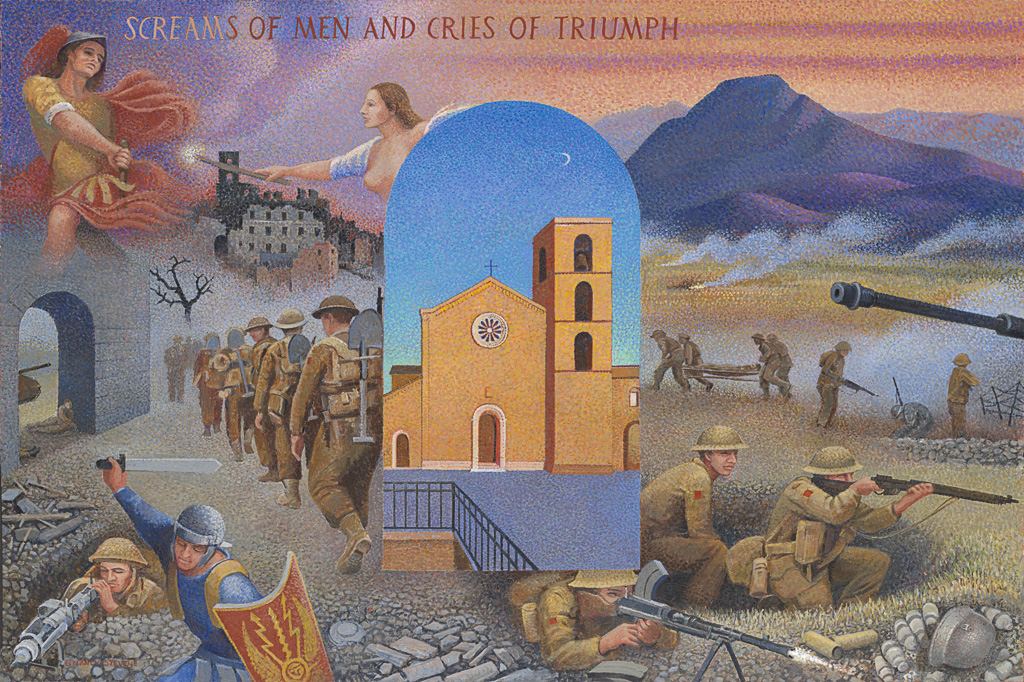

SAN PIETRO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

SAN PIETRO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

With the enemy cleared from the mountain ramparts, the British Eighth Army with 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade and US Fifth Army fought from winter to spring to break through the bottleneck into the Liri Valley. On the slopes of Monte Sammucro below Hill 720, the heavily defended village of San Pietro was bombed, fought over several times and destroyed. All Italian males from 15 to 45 were evacuated to work on German defences. Five hundred elderly, women and children fled to mountain caves. With little food and water, 140 starved and died. Survivors left the shambles of their village and rebuilt nearby after the war. Many emigrated to Montreal.

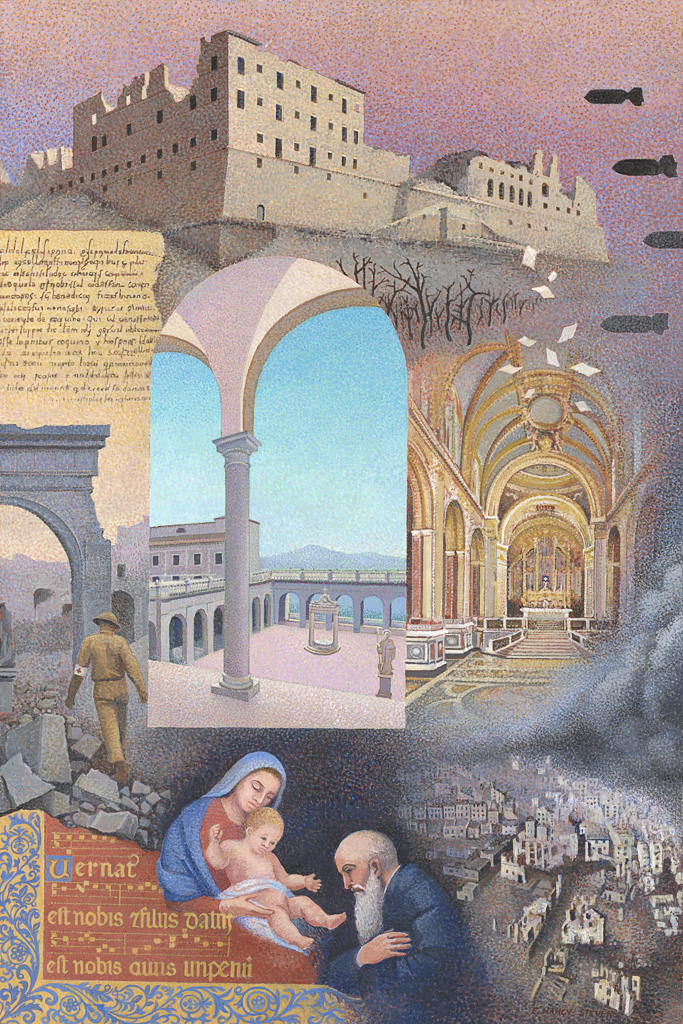

MONTESCASSINO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

MONTESCASSINO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

The Allies destroyed the Abbey of Montecassino, one of Christendom’s most venerated shrines founded by St. Benedict 15 centuries ago, and the town of Cassino below. “You could see aircraft going in and smoke over the mountain from the shelling. There was a lot of talk among the guys about how stupid it was. They wasted so many men when they could have gone around it,” said Jim Holman of the 48th Highlanders. Valorous infantry, particularly the Polish, cleared the last great obstacle for assault on the Hitler Line. German gun and observation posts ringed the slopes but not in the abbey. The Germans before the battle moved rare books and works of art to the Vatican, including the monastery’s first document in the Italian language, but loss to the world was priceless.

PONTECORVO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

PONTECORVO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

“We’ve just finished the best job done by the Canadians in this war, and maybe in any war. In thirty-six hours the 1st Canadian Infantry Division smashed, over-ran and passed through a defence line the Germans assured the world was the most impregnable ever built,” wrote Farley Mowat of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment.

The Hitler Line was breached near the town of Pontecorvo, built two centuries before the birth of Christ. Canadians rang the cathedral bell after 1st Infantry Division and 5th Armoured Division fought a chaotic battle in fog and smoke where guns of friend and foe pointed in all directions. It was the single bloodiest day of the Italian campaign. 1st Division alone suffered 879 casualties. “They went in and after the battle was over, I think there was only 67 or 69 or 70 troops reported back to regimental headquarters,” remembered Sydney Frost, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry.

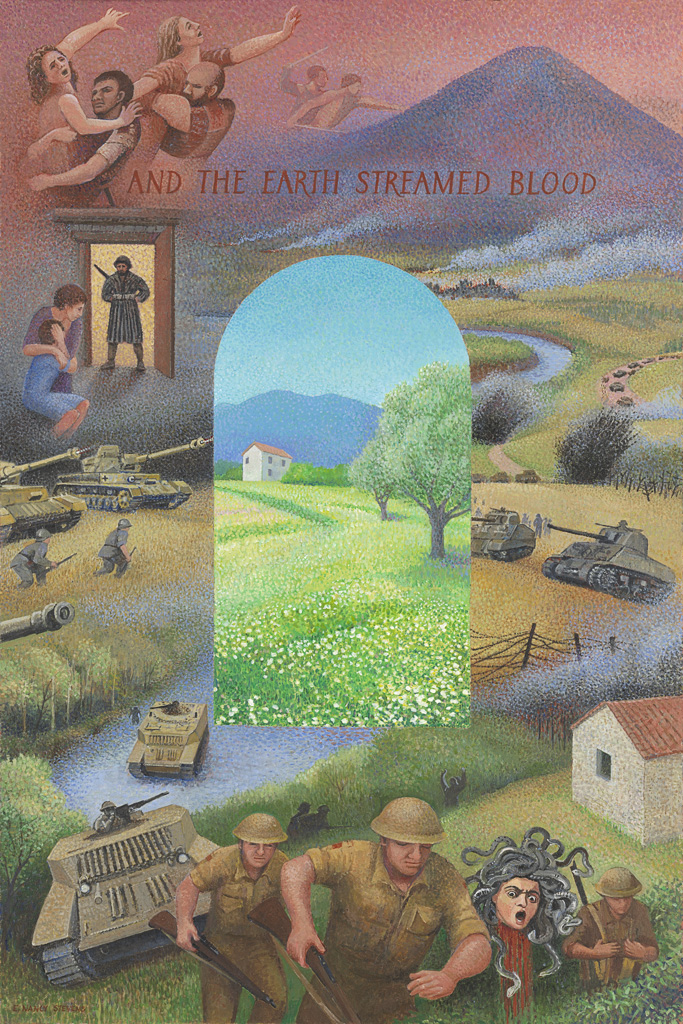

MELFA 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

MELFA 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

Ten kilometres beyond the Hitler Line, infantry and tanks fought furious battles to cross the Melfa River above its junction with the Liri River. In the Arunci mountains to the west, another savage violence of raping of thousands of Italian women and children by North African colonials of the French Expeditionary Force accompanied its advance to cut off the Germans.

Lord Strathcona’s Horse reconnaissance troop commanded by Lt. Edward Perkins seized a small bridgehead across the Melfa River in Stuart (Honey) tanks with turrets removed for .50-calibre machine guns, followed by a Westminster Regiment company commanded by Major John Mahoney. Under heavy fire from Panther tanks, rockets, mortars and machine guns, they held the crossing until reinforced the next day. Major Mahoney was awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry, Lt. Perkins, the Distinguished Service Order.

IN PURSUIT 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

IN PURSUIT 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

Fighting as fierce as on the Hitler Line widened the tiny Melfa River bridgehead. “Our guns got so hot we threw buckets of water on the barrels and had to cut our firing from seven rounds a minute to two,” said A.C. (Tommy) Thompson, 1st Medium Artillery Regiment. The narrow battleground crowded by the pursuit of the stubbornly resisting Germans required another bridge across the Liri River seven kilometres away. Built by engineers under fire for two days, the reinforced 120-foot Bailey bridge buckled and collapsed into the river. “We felt pretty low because we were leading the attack, lifting mines and making roads, and it held up the attack for a day,” said John Dent, 1st Field Squadron, Royal Canadian Engineers. “I used my engineers like infantry,” said Major-General Bert Hoffmeister, commander, Fifth Armoured Division.

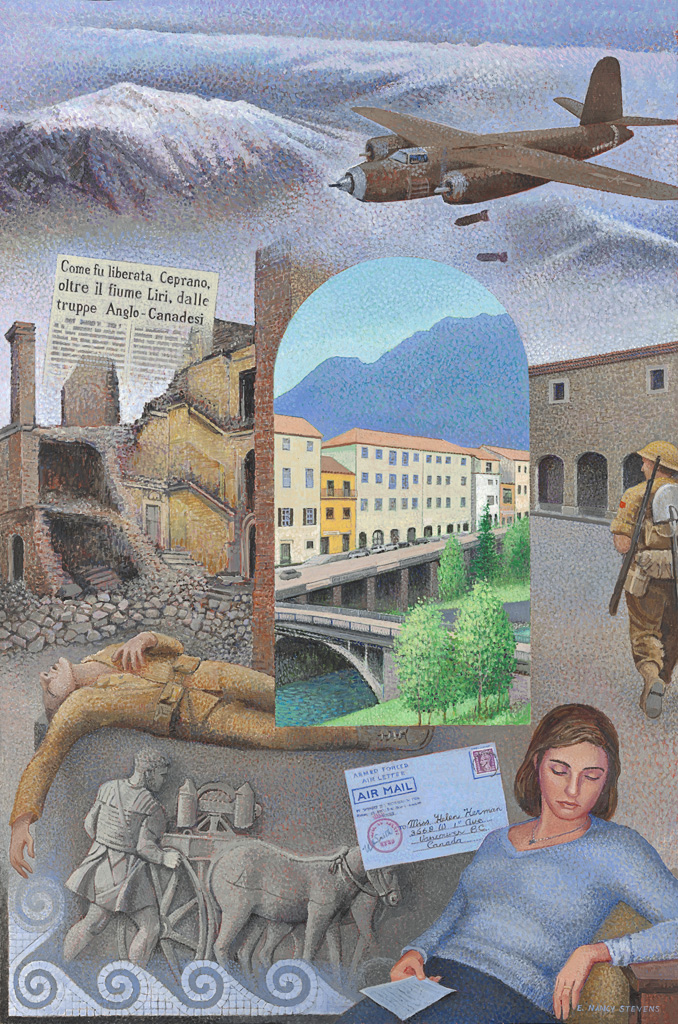

CEPRANO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

CEPRANO 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

The main battle for the Liri Valley was over with the 1st Infantry and 5th Armoured Divisions across the Melfa River. Their next objective was to cross the upper Liri River near the ancient Roman town of Ceprano. Its bridges and buildings had been destroyed or heavily damaged by shelling and bombing. “I lost four or five friends in that battle, too,” said Fred Scott of the Perth Regiment which crossed the river under fire in boats to clear the town. August Meacham of the accompanying Cape Breton Highlanders remembered his company commander: “He showed me pictures of his family as we crouched behind a stone. It said a lot to me at 20 years old. Capt. Archibald was killed quickly by an exploding shell before we had gone 20 yards.”

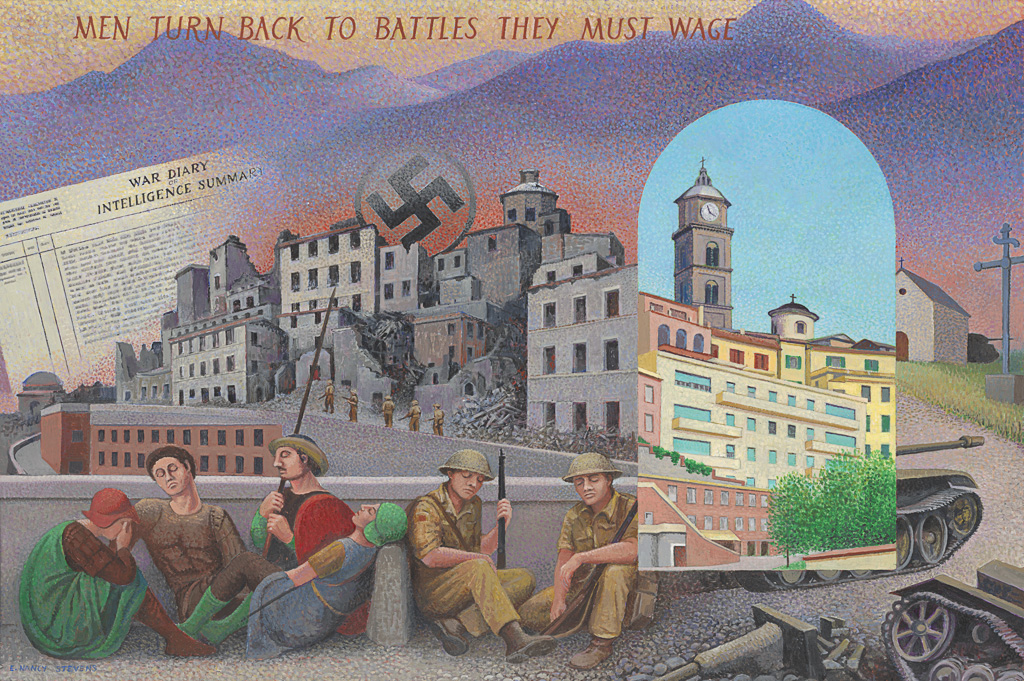

FROSINONE 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

FROSINONE 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

The campaign ended June 4 when the Canadian-US 1st Special Force—the Devil’s Brigade—led the US Fifth Army into Rome. The 1st Division had been in combat almost continuously for 11 months. On June 6 Canada’s 3rd Infantry Division landed on the beaches of Normandy to liberate North-west Europe. German tanks blocking the main highway to Rome were destroyed by tanks of Lord Strathcona’s Horse. “I lost five of my friends there,” said Robert Greene, “and we buried them right next to the little church at what we called Torrice Crossroads.” The same day Lt. Everett Simm of the Loyal Edmontons was killed by a sniper as he led a patrol into the German communications centre of Frosinone. It was his first day in action, and one of the last casualties of the Liri Valley campaign.

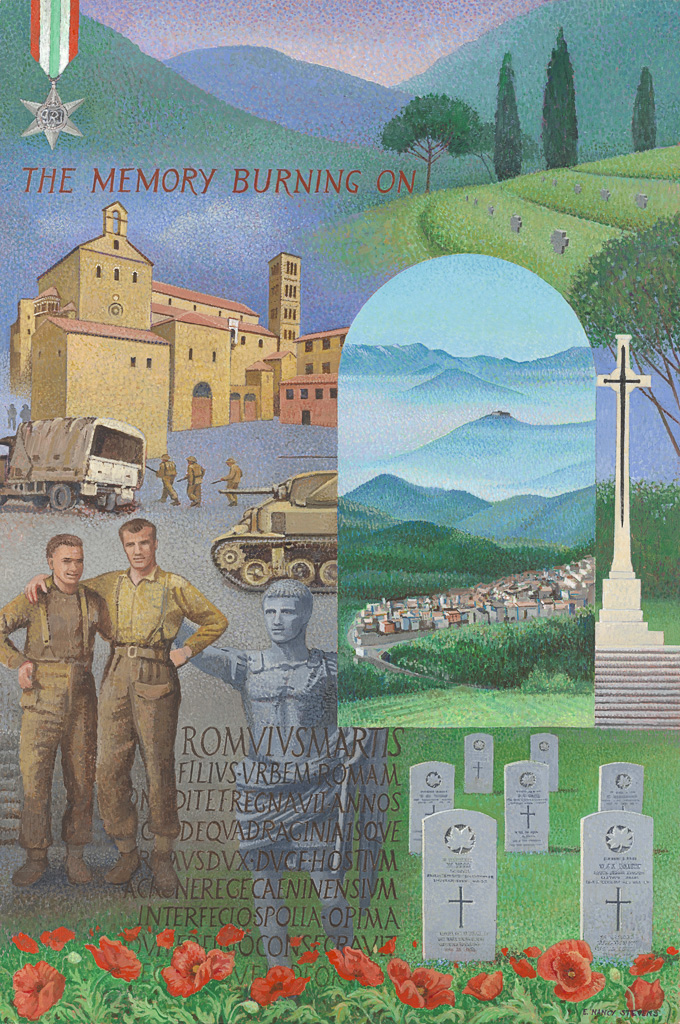

LIRI VALLEY 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

LIRI VALLEY 61 x 91.5 cm acrylic on board

Canadians went into reserve near the pre-Roman hill town of Agnani except for 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade in support of British and Indian divisions in the chase north of Rome. There were still another six months of fighting, mountains and rivers to cross before the Italian campaign was over. “The Canadians were good fighters,” said Robert Dietz of the German 76th Panzer Corps who emigrated to Nova Scotia after the war. “They were up against our best soldiers, including the 1st Parachute Division, and they never stopped coming at us.”

Canada lost 789 men killed, 2,463 wounded in three weeks of the Liri Valley campaign. Allied casualties to liberate Italy were 312,000, the equivalent of 40 per cent of total Allied losses in North-west Europe. No campaign in western Europe cost more in terms of killed and wounded than those suffered by infantry forces in Italy.